Frederick Jameson states towards the beginning of “Utopia as Method” that he does not believe “the postmodern city…[to] encourage thoughts of progress or even improvement, let alone utopian visions of the older kind” (20-21). So what discrepancies between the modern and the postmodern make the latter so discouraging? Probably the recent move towards skepticism – postmodernism is essentially a way of thinking based in challenging assumptions about the objectivity of truth and knowledge, which can be useful until it gets too self-involved: creating a discourse centered around empty criticism and making forums for blame out of spaces for learning.

This postmodern attitude is pretty self-absorbed, and pretty chaotic. Since whatever we might have believed to be Certain And True has been revealed as heavily institutionalized and learned, it becomes difficult to have faith in…anything, really. This gets to be a ridiculous hindrance to doing anything productive, particularly because it’s easy to dissolve into nihilism and cynicism when thinking too hard about it. It’s also so easy to think too hard about it because the wealth of information available in this information age is rife with unsavory facts. That’s the crux of cynical reason – we’re all hyper-aware of why we’re being such sticks in the mud, but are too tired and resigned to being sticks in the mud that we can’t figure out anything else to do.

Graphic found using the “random page” function on WikiMedia Commons. Over 30,000,000 media files are currently available on the database, and an entire hour spent clicking the random page button only gets you a few hundred results in!

And so hence chaos and the self-conscious embracement of. Jameson characterizes the postmodern city as a place “in permanent crisis [which] is to be thought of, if at all, as a catastrophe rather than an opportunity” (21). It can be observed from Donna Goodman’s survey of the past few hundred years in her book A History of the Future that periods of crisis are nearly always followed by a period of economic, technological, and moral upswing, so is this just a waiting game? Where do we put our faith? The only really infallible logic I can think to name is math. Logic that glaringly, comically logical, however, certainly has a place in utopian visioning. Think patterns: grids, fractals, radial organization. The panoptic architectural and city plan and all its suspect connotations, the legibility of Manhattan’s grid system, the great big spiral of Parisian arrondissements. The literal grounding force.

Paris’s numbered arrondissements

A drawing of a panoptic plan

The city was certainly a frontier in the past, but is it still? The romance surrounding Manhattan is still alive and well but it’s primarily nostalgic. New York City was so inspiring as a frontier because it is awe-inspiring – it creates an overwhelming environment in which possibilities are therefore permitted be overwhelming. There’s a definite tension in the city between the preservation of the old and exciting – what was cutting edge when it was built and signified a spectacular and modern attitude – and the new and “user-friendly,” which invites you, its fortunate visitor or inhabitant, to project onto it in such a way that it becomes exclusive. The blocky-looking condos going up right next to Katz’s Deli, for example, are so luxury-dull from the exterior, so clearly a prices-starting-at-$1 million situation, that they limit who can reasonably imagine themselves inside.

Rendering (by Williams New York) of completed condos

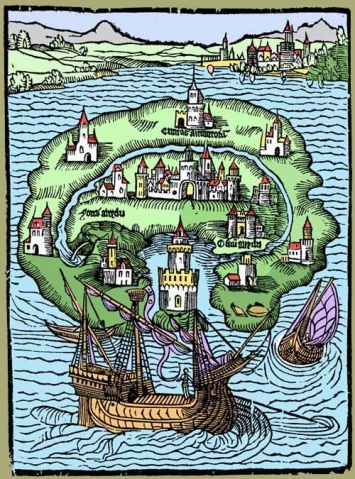

The city is (or perhaps was) such a useful template for a model utopia because it’s so compact and complete – everything you need to live in reasonable comfort is readily accessible, and often the only pressing reason to leave is simply to Get Away. Many socialist spatial utopias are based upon this idea of a tidily contained lifestyle, both realized and not. Thomas More’s fictional Utopia is an extreme example, contained entirely to an idyllic, manmade island. However, completely encapsulated ways of living are not common in the real world – and for good reason.

An illustration from More’s Utopia

In Sex and the City, one of the guy-types Carrie qualifies as an undateable freak is “Manhattan Guy,” who never leaves the island – ever – and doesn’t see why anyone would want to. His total contentedness with his circumstances is bizarre, uncanny – means for rejection by reasonable city women. “Spatial play” utopias generally seem to concern themselves with the maintenance of contentedness, usually alongside the creation of beauty and tidiness. Sometimes they’re even imagined into already “content” realities. The freakiness of this is pretty undeniable, though, since these qualities are also usually enforced by means of an implied totalitarian regime. Manhattan is obviously not an isolated totalitarian regime, but Manhattan Guy is still freaky for the same reason the citizens of these imaginary utopias are freaky: they are either complicit in or ignorant of what makes their situation unsettling.

That unmistakable skyline in the opening credits

But these types of self-contained spaces have been physically built, as David Harvey asserts in Spaces of Hope. He cites Disneyland and the shopping mall as prime examples of escapes into the world of spatial play. Disneyland is more explicitly a Moreian, sanitary, constructed-for-singular-escapist-purpose zone since it goes so far as to make its own mythology – the only heritage discernible within Disneyland is that of Disney itself. The mall, though less extreme, has a similar effect on its visitors, since both are essentially environments “designed to induce nirvana rather than critical awareness” (168). These spaces are, above all else, organized with the objective of being as inoffensively pleasant as possible. Furniture showrooms and pre-furnished or model homes can also be included in this category of fantasy space, since they create the same sort of passive, idealized zone, ready to be projected onto. Their objective is to make you want to live there – to feel at home even though none of this stuff is really your stuff.

A little vignette in Bed, Bath & Beyond (with a sign instructing the store’s patrons not to actually rest on the bed)

As of 2011, you can live at Disney World – if you have $2 million or more to blow on a luxury home at Golden Oak, a residential community within the Florida resort. The Golden Oak website touts it as having all the usual trappings of a gated resort community, plus the inimitable Magic Of Disney. You’re not permitted to lease the properties; you have to buy. It’s a long-term commitment to a retreat.

Think of all the organized fun to be had!

The ability to live in a place like that is unsettling because it marks a movement from the realm of playfully exercising fantasy to the actual enactment of fantasy – a fantasy so total that it’s hard to see it from the outside as anything other than delusion. It goes beyond the worrying exclusivity of any other gated community because of its location in an invented reality. Golden Oak residents elect not to live in The Real World.

A far sneakier example of gated community-type exclusivity is Uber, the poster child of the sharing economy. The company’s promises of convenience, inclusivity, and the cute fairness of “sharing” put it in the family of socialist utopian visions. Uber has recently begun to reach beyond its well-established role as Easymaking App into the realm of metropolitan transportation systems. It’s working to develop technology that could mark movement towards driverless cars, has implemented a system of discounted ride sharing, and has begun testing a new kind of sharing option called a “Smart Route” that works more like a bus line than a car service. In a blog post on February 2nd of 2015, Uber cited its partnership with Carnegie Mellon University in an effort to develop advanced technologies as paramount to its “mission of bringing safe, reliable transportation to everyone, everywhere.” Not content with just being a taxi service, Uber wants mass transit’s business.

A satisfied independent contractor on the Uber website’s homepage (Uber doesn’t classify its drivers as W-2 employees)

What Uber seeks to create, essentially, is a city with limited options. Unlike established bus and rail systems, there would be no way for the poor to use it. No found MetroCard or amassed change can get you in an Uber; you need a smartphone, a credit card. And since you need to own and maintain a car to be an Uber driver, it’s not a viable moneymaking option for anyone who can’t do so. By creating this new level of convenience for those who can afford it, members of the lower class are taken totally out of the picture. And if those who can afford to are choosing Uber over public transit en masse, funding for public transit will inevitably decrease, worsening conditions and limiting its reach. Traveling in the backseat of Joey’s pine-scented Honda Accord rather than the downtown 6 train also permits you blissful ignorance of parts of the city that you don’t want to see, rendering the poor all but invisible to those they’re not convenient for.

One of the primary goals of imagined egalitarian utopias of the past is for there not to be any poor, but it’s pretty clear by now that that’s not feasible. Actually enacting any sort of spatial utopia is just making the poor harder to see. But utopian visions such as these are valuable when they stay visions, serving not as methods of fixing but, as Jameson proposes, methods of play.

Sources:

Craig. “Uber and CMU Announce Strategic Partnership and Advanced Technologies Center.” Uber Newsroom (blog), February 2, 2015, http://www.newsroom.uber.com/uber-and-cmu-announce-strategic-partnership-and-advanced-technologies-center/

Disney Golden Oak, accessed 12 March 2016, http://www.disneygoldenoak.com/

Goodman, Donna. A History of the Future. New York: Monacelli, 2008. Print.

Jameson, Frederic. “Utopia as Method or the Uses of the Future,” Utopia/Dystopia: Conditions of Historical Possibility, Edited by Michael D. Gordin, Helen Tilley, Gyan Prakash. 2010. Print.

Nisenson, Lisa. “Uber’s New Wave of Urban Design. Are Cities Ready?” Mobility Lab, last modified September 8, 2015, http://www.mobilitylab.org/2015/09/08/ubers-new-wave-of-urban-design-are-cities-ready/

Plitt, Amy. “Construction Begins on Condos Rising Alongside Katz’s Deli.” Curbed New York, last modified January 5, 2016, http://www.ny.curbed.com/2016/1/5/10849620/construction-begins-on-condos-rising-alongside-katzs-deli/

I am glad to see that you connect and re-connect to Jameson’s proposal that utopias be seen as “methods of play” rather than taken as literal visions of the future. My understanding is that these visions of utopia are interpretations of the social, economic, and political ideas the creators would hope to see in a future, if not their own future. In other words, a broad suggestion with specific contexts for realization. Regardless of whether some elements of these future visions have, or may, come true, perhaps it would be worthwhile to establish a timeline between the conception of a utopian vision and the expectation of its validation. You mention the notion of nostalgia within the context of actual cities, such as New York City, and I can’t help but think that the “romance surrounding Manhattan” is entirely validated by the present rather than reliant on the past. While I would agree that New York introduced the romantic narrative of a young twenty-something moving to the city, scraping by at 3 jobs, and finally “making it”, I think it still maintains the standard for this story, for every twenty-something, in every city. In that way, New York City still holds on to its original utopian ideals, without demanding sole responsibility for the future landscape. What I do find interesting (and slightly unsettling), are completely manufactured communities like Golden Oak in Disneyland. In contrast to NYC, Golden Oaks boasts a high price tag for a high standard of living, and unfortunately, no authentic experiences. It would be one thing if the community were a completely imagined other-world, with an invented food culture or new democracy. At least then it would bring something new to the existing cultural landscape. Yet, even the architecture of Golden Oak is said to represent the “timelessness of Old World and Old Florida”, making the the community itself an expanse of cultural appropriation accessible only to a few. In this case, I think Disneyland has relied solely on nostalgia and inaccessibility as a selling point for their vision of a utopia. They have successfully branded Utopia as a commodity, much like Uber has monopolized “public” urban transport, and I wonder: Are we moving towards a future where business and governance collide?

LikeLike

It is true in cities that maintain utopian ideals, like New York City, people are required to use their imaginations in order to compete, survive, and potentially “make it”. What I find most interesting is that the definition of “making it” varies by individual; in a city as receptive as New York, everyone can seek their own utopia there. What I also think is worth mentioning is Jameson’s observation is that what matters in utopias is not the imagined, but the “unimagined, the inconceivable”. Cities all represent new frontiers, for the people that build and design them and the people that come to inhabit them. But they are also full of chance, unexpected outcomes. The sites provide “spaces of play” but cannot guarantee an outcome of success and outcome. I suppose this might link back to your statement of the post-modern city being a place of “chaos rather than opportunity”, and inherently becoming a place of stratified experiences and narratives, simultaneously connoting adventure, glamour, success, danger, poverty and struggle.

The example of Golden Oaks at Disneyland I thought was a perfect example of fabricated “reality” that intends to breed fabricated contentedness of “spatial play” that is entirely false. As opposed to living in a large metropolitan city (like New York or Los Angeles, etc.) where you either “make it or break it” based on your ability to compete in whatever social or economic context you find yourself in, at Golden Oaks the game is entirely fixed. There is no need to compete once you are there; considering the cost of purchasing a property and having the ability to make such a huge commitment Golden Oaks represents a reward for already having “made it”. This is the ultimate prize for achieving success in America; an isolated refuge from cities and interaction from the variety of people who are there struggling. Again, the unimaginable is important here: the utopia is a closed system, and is just as likely to breed dissatisfaction as it is to breed happiness. The fabricated contentedness of this overly structured spatial play generates a fantasy space that is designed to make residents more submissive and passive. As you noted, this kind of paradox is also present in Uber, which represents itself as committed to sharing, inclusivity, and friendliness. But the inherent economic bias for participants (being able to afford a car to be a driver, and having a smartphone and credit card to be a customer) and the ability to choose routes so as to gain select views of the city you are passing through (avoiding lower income areas) makes it an exclusive classist enterprise. To me, this ability to selectively choose what we want to believe as real or true is also a post-modern condition. I think it also present in the rise of Internet culture, especially networking sites like Facebook, which allows you to choose what you want to see and hear about most often in the world and subsequently provides “suggested posts”. This creates an opportunity for an intellectual utopia of sorts.

LikeLike

You start to set up two ends of a spectrum of the sharing economy – envisioning utopia and indulging in fantasy. A company like Zipcar could be on one end, because it offers a novel service for the sake of environmental progress. You’ve made a great case for Uber as a fantasy indulgence. Companies like AirBnB could be in the middle, because the host doesn’t become indentured to the service but still only provides housing for middle and upper class individuals.

There’s an understated but important connection between the first half of the essay to the conclusion, that the sharing economy (like Disneyland and shopping malls) plays into a consumer’s desire to acquire objects associated with a certain lifestyle, which we may or may not be able to afford. We have preconceived notions of what luxury may be, and these companies tell us we can rent it for a small fee. We can’t all live in Golden Oaks, but there are private islands for $100 per night on AirBnB. The sharing economy closes the gap between superlative luxury and upper middle class bank accounts by decreasing the amount of time these experiences are available to us. Consumers expect Ubers to feel like private cars, AirBnB’s website advertises stranger’s apartments as vacation homes, but the likelihood that these expectations meet reality is low.

The separation of working class and middle/upper class could also become more vivid if you brought some of the ideas from Four Futures into your vision of how Uber is bisecting cities. also, I’d push through at the end with a few more unconventional ties from the reading to the present. I’d be curious to see what other services or goods were meant to connect people but ultimately externalized costs to marginalized groups.

LikeLike

I appreciate how you not only bring up present-day spatial play examples of attempts at a particular version of utopian idealism, but you also begin to touch on the psychological and ideological effects of this spatial play. You begin to draw a connection between manipulating the physical space of the consumerist city and the psychological manipulation of the inhabitants of that space– how does one think about the utopian effort in which they live? If it’s impossible to craft a utopian reality enjoyed equally by every citizen in a society (as we see in Peter Frase’s “Four Futures”), are these attempts at utopian realities simply attempts at instilling ignorance in its inhabitants? Is utopian spatial play really about creating a space of delusion towards the shortcomings of society’s systems? Your examples of the Golden Oaks gated community and shopping malls could support this thought. Communities like Golden Oaks may be more concerned with achieving an illusion of perfection and utopian ideals, rather than actually striving for a society that is fair and equally enjoyed by all citizens, despite social divides. In a similar way, shopping malls are actually designed without windows so that shoppers are not able to see temporal signals from the weather about the passing of time, such as the sun going down. By being unaware of the passing of time, shoppers become psychologically trapped in this consumerist space, and spend more time than they had originally planned in that micro-society. I appreciate how you begin to touch on how utopian spatial play often results in a space of delusion and psychological manipulation, and I’d like to see that point be pushed further with some of the theory found in the readings.

LikeLike